The modern state typically inspires two antithetical interpretations. Progressives see the state as a means to restrain capitalism, level the economic playing field, ensure equality, and liberate the individual from the dead hand of traditional forms of marriage, family, and sexual morality. Conservatives see the state as a threat to personal freedom and inherited values, at best a guarantor of property rights, free markets, and equality of opportunity. In a sense, both are right. Both are also deluded.

Human happiness depends not on maximizing individual rights and liberty, important as both are, but on ensuring complementarity among persons—achieved by a lengthy and sometimes arduous process. We conceive of that process as culminating in a shape, and as similar to the folding of a flat sheet of paper into three dimensions. Thus, this essay’s guiding metaphor is of a folding process that shapes us into persons who “fit with,” mutually support, and depend on one another.

We argue that this folding process can take place only in hierarchy; markets cannot direct it. When markets encroach on hierarchies and reallocate resources away from them, society suffers. When hierarchies are properly protected and empowered, society flourishes.

It is in the nature of the modern state to augment markets at the expense of the hierarchies that fold the soul. Both progressives and conservatives fail to see this. Both fail to see, as well, that the choice between statism and free markets is a false one. In practice, the state and market rise together, and their rise is accompanied by decreased hierarchical formation and decreased complementarity among persons. Reversing this trend is imperative.

Aristotle and Aquinas recognized that a person’s happiness depends on his proper “functioning”—on the orientation of his acts toward the ends proper to man. In nature, function coincides with shape. We can infer function from shape, and shape from function.

So it is with the human soul. The mature soul achieves a complex “shape” that fits with other shapes—other souls. We learn manners and are shaped by customs. We acquire a common language and habits of mind that “fit” our social circumstances. These shapes, which often take the form of the standard set of virtues, drive all shared and fruitful human action: marriage, family life, and civic activity. The particular shape of a man’s soul “matches” with other particular shapes. The husband dovetails with his wife. The roles of father and mother shape adults in ways that fit with the only partially shaped lives of children. Students are trained to have dispositions that accord with those of their teachers. These matches overlap with other matches to create productive social configurations, making for a functional society. Upon such matches, and so upon complementarity, our happiness depends.

To speak of the soul’s having a “shape” may seem odd, but it should not. Shape governs a large domain of activity in nature. Atomic binding depends on shape. The DNA-protein interactions that regulate physiology depend on shape. Social science sees the human person’s objectives and choices in terms of shape.

Shape plays an important figurative role in philosophy and theology. Critics often describe the modern soul as “flat.” José Ortega y Gasset spoke of modern man as “narrow” and “hermetically enclosed.” Richard Weaver argued that the metaphysical right of property (as distinct from the contractual right of capital) “imprints” itself on the soul. Zygmunt Bauman describes modernity as “liquid.” Theologians explain baptism as “marking” the soul, and religious thinkers speak of spiritual “formation.” We are formed (shaped) by the leading ideas in our culture.

Achieving a proper shape for the soul involves a forming or folding that occurs over decades. There are many possible soul shapes, starting from the way in which we’re first folded into simple shapes as small children, then refined into more complex, beautiful, and complementary forms as adults.

This shaping can be expressed in the metaphor of origami. Our souls are creased, first this way, then that. This process of folding gives us varied, complex, and ultimately complementary shapes.

Though some soul shapes are naturally prized—souls shaped by justice, prudence, temperance, and fortitude, for example—people seem able to be molded (and mold themselves) in a great variety of ways. Though the tradition of origami contains a number of set figures (the crane shape, for example), mathematicians have shown that any shape can be produced through the folding of a single flat surface. Something similar holds for souls.

In the folding process, some steps must precede others. The choices made for a person (especially the child), and those made by a person in his early years, provide the bases for later choices and for character. The soul’s development is path-dependent.

The metaphor of origami captures this sequential aspect. In the Republic, Plato focuses on the education that forms us to live in community. We may disagree with his ideas about what kind of people we should become (and what kind of community we should seek). But he was certainly right that formation is essential and that good education requires proper sequencing, in addition to proper content. Plato argued, for instance, that music should be the first subject taught to children. By his way of thinking, excellence in music folds the soul in a way that prepares for future folds, which guide us in the pursuit of truth, beauty, and goodness. Similarly, to create the crane from a sheet of paper, we must make exactly the right set of folds at the outset, and continue in the proper sequence.

The metaphor of origami also illuminates the truth that the soul’s development produces richer dimensionality as life proceeds. Origami converts a two-dimensional geometry into a three-dimensional one. As Paul says, we are to leave behind childish simplicities and enter into the adulthood of conscious participation in the spiritual dimensions of life. The generic sheet of human paper, our created condition, needs to be folded many times, until we become multifaceted, complementary, Christ-like figures.

Each fold in origami imparts information to the paper. The information is expressed in the emergent structure. This information, or structure, is a constraint—a limit on outcomes and on choice. This is true of shape in general: It is a constraint on function because shape implies certain interactions and excludes others. The relations among folding, shape, and information are most evident in DNA. The folded shape of a DNA molecule determines its function by limiting its interactions with other proteins. The DNA’s shape contains an organism’s genetic information, which in turn “reads” the information in the shapes of other proteins, matching up with them when they are suitable—which is to say, complementary.

In every origami sequence, early folds constrain (inform) later ones. The earliest folds shape the largest proportion of any intended structure. They embed the most information, and they most profoundly affect the final structure and function of the origami project. We can’t get halfway through the folds that produce a crane, then decide to make it into a pagoda.

In the origami of the soul, the crucial early folds happen during childhood. They have a lasting influence on our souls, which is why a child’s future depends on parents, especially mothers, who devote themselves to the folding of their children’s souls.

The parent-child relationship is hierarchical. So are other relationships in which folding occurs. After childhood, folding continues in hierarchical settings. Wives form their husbands. Husbands form their wives. Schools fold souls. Communities and kinship networks do the same. Folding is the special business of religious institutions. The military is another powerful soul-folding institution. Both the church and the military view the formation of their key members—clergy and officers—as of fundamental importance. The very language used by parents, schools, religious communities, and military institutions to describe this activity—the word “formation”—shows that these institutions are designed to embed form, to in-form. They seek to fold the soul into a shape suited to a specialized role in relation to others.

The information needed for this form-embedding cannot be read out of books. Our moral, civic, and intellectual virtues represent a crucial form—a kind of information—inculcated by hierarchical institutions through the constraints (shame) and incentives (honor) they place on the developing person. This information is decisive for human flourishing because it gives us complementary shapes, allowing us to play our roles without debilitating friction.

The soul’s folding happens only within hierarchy. Markets do not, indeed cannot, fold the soul. Certainly, markets use prices to channel human behavior toward some activities and away from others. But the information contained in prices is not rich enough to inform our souls. Why not?

First, by their nature, folding and complementarity are highly personal. This is why hierarchical folding institutions operate through the exercise of particular kinds of authority by particular people in particular instances with particular information. By contrast, in well-functioning markets, price information is impersonal and circulates impersonally. It summarizes, or (as economists would say) aggregates, information that is common to all market participants.

Furthermore, prices emerge only in markets of sufficient mass, or “thickness”—markets with enough participants to render individual motivations and desires inconsequential. Market prices are known to carry flawed information in small (or “thin”) markets. A well-functioning stock exchange tells us the “market” price of a stock, not Warren Buffett’s price.

Thus, markets depend on information that differs fundamentally from the information embedded by hierarchical institutions. Prices cannot carry the information that shapes a person’s soul. It follows that markets cannot direct folding.

Markets can also work against the origami of the soul. They do so by engendering specialization, and through it economic growth. New and more specialized forms of production, and new possibilities for consumption, cause markets to grow. We may assume that growth is good. But economic growth is not simply an increase of goods, supplied and consumed in the context of a single vision of the good life. Rather, it encourages the proliferation of (often contradictory) conceptions of the good life. This proliferation is often considered a gain for liberty, since it means that we can undertake more of what John Stuart Mill called “experiments in living.” But the results are paradoxical.

The life paths, or soul shapes, made possible by economic growth are far more numerous today than they were even a few decades ago. Ever-greater technological mastery, encouraged by the market economy, makes accessible an array of soul shapes that previously were unavailable to most. The contraceptive pill made recreational sex more widely available, for instance. We may soon possess technologies that will enable the reversal of sex characteristics, or allow for the “writing” of a person’s genome.

This process seemingly empowers us. But in doing so, it generates entropy—the de-formation of a social system. Economic growth leads to a loss of information at the level of the soul, which in turn causes the unraveling of social structure, which in turn causes the further loss of information to the soul.

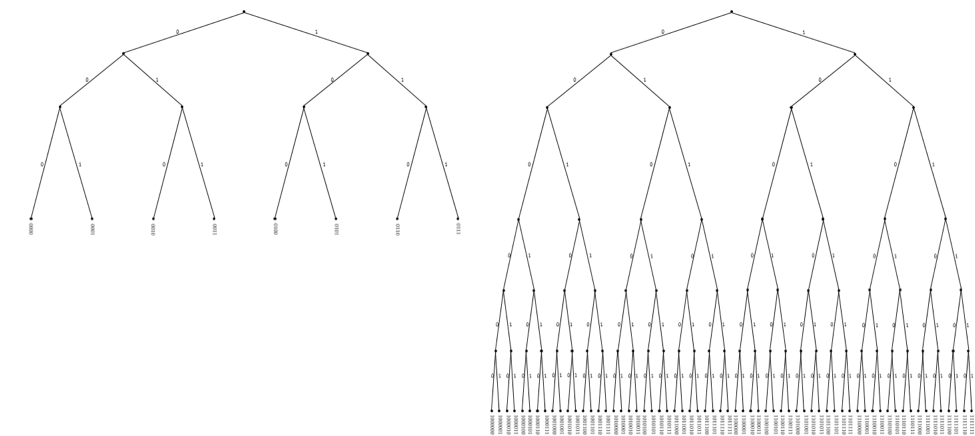

Consider the illustration below. Economic growth moves the person from an environment in which, say, eight life paths are available (the left-hand diagram) to one in which a branching set of paths has, say, 64 possible outcomes (the right-hand diagram). A person at the topmost node of the right-hand diagram has more choices than does his left-hand counterpart, but he must therefore overcome twice as much entropy. Only half as much information, or structure, is available to a person on the right as to a person on the left. Market-driven growth increases personal confusion by increasing the number of available life paths, or soul shapes.

The twin facts of decreased social structure and increased entropy may explain some of the problems we face today. Charles Murray gives a persuasive account of the widening gap between the functional people in the upper deciles of our society and the dysfunctional people lower on the social scale. In a low-information, high-entropy cultural context—our context—people increasingly lack structural information. As Matthew Crawford insists, they lack “cultural jigs.” Jigs are tools used to impart structure to wood; cultural jigs are set patterns of life that give structure to our souls. As entropy increases, people will need ever-higher IQs and ever more social and financial capital in order to find their life paths. High entropy means that ever more men on the margins won’t make it past adolescence. They will get stuck in half-completed origami projects.

Decreased information and increased entropy may also help explain the rise of mental illness among talented young people. Given the wealth and opportunity our society provides them, our well-educated young people ought to be the happiest generation in human history. But the opposite seems more nearly the case. Young people must deal with the stress of trying to advance in a society that is uninformative and entropic.

Folding institutions, by contrast, exist to promote a particular conception of the good. They are not monolithic, but like the left-hand diagram below, they offer a limited set of paths. They exist to guide us on a “narrow way.” Their limitations paradoxically make for more “informed” individuals. People shaped by hierarchical institutions encounter less entropy, and they have a road map for life embedded in the shape of their souls.

We face a further problem. Because market processes lead to economic growth, and economic growth increases returns to market activity (largely expressed through higher real wages and lower real prices), the expansion of markets and resultant economic growth increase the “opportunity cost” of non-market (hierarchical) activity. It is harder and harder for mothers to specialize in folding their children’s souls when the market value of their time in lost wages rises higher and higher. It is harder and harder for fathers to restrain their work activity when the returns on their labor rise apace.

This dynamic affects all hierarchical institutions. We complain that there are no more “statesmen.” Why did they disappear? Because the returns earned by talented men and women in the market are greater than ever, whereas the returns earned by talented men and women in public service, returns measured in honor and respect, have remained the same for decades. Joseph Kennedy made money, but he wanted his sons to run for public office. Today’s billionaires want their sons to run the family office, managing wealth. Upper-middle-class parents are affected as well. They recognize the shift in rewards, and aside from excellent schools that are seen as indispensable for financial success, they invest less in hierarchical institutions for their kids. Boy Scouts, Little League, and church camps are sidelined in the formation of today’s elite children. Attention is given to preparing them to be agile market competitors.

In short, markets take resources away from folding institutions and give them to firms and consumers. Markets have a flattening and “enmassing” effect. They defund the formation of children (and procreation itself) by capturing ever more of the ambition, attention, and desires of parents. Markets redistribute resources from civil society as well, focusing human endeavors ever more on production and consumption. The dual-income household is simply the most obvious example of this cultural defunding and reallocation of human resources toward market activity.

Economists regard market activity and the work of hierarchical institutions as the two primary modes of human behavior. Further, economists construe markets and hierarchies as separated by a “boundary line.”

If it is true that the soul’s folding—its work of achieving a complex, complementary shape—can occur only inside hierarchies, it follows that the position of the boundary line separating markets and hierarchies is one of the most important characteristics of any society. Depending on the position of the boundary line, a society either gives the soul room to fold or it does not.

Thus, the most important question as we consider the social implications of markets is not whether markets are over- or under-regulated. Nor is it whether we should have some version of capitalism or of socialism (though we admit the importance of this question). Rather, the possibility of a good society turns most on the placement of the boundary line between markets and hierarchical institutions. The most important question for us today is whether the last two centuries of market expansion at the expense of territory once held by hierarchical institutions have resulted in an under-allocation of societal resources to interior goods that require folding and an over-allocation to exterior goods provided by efficient markets. Have markets left enough room for hierarchy and its work of folding the soul?

Contractual innovations, innovations in how firms organize themselves, the globalization of capital and labor markets, and advances in information technology have led to a long-term advance of markets. Consistent with the thinking of economist Ronald Coase on the boundary line between markets and hierarchy, we can say that this advance has occurred at the expense of non-market institutions. That’s because the relative costs of market transactions have declined.

For example, it is far less expensive to buy and sell ownership shares in companies today than it was only a generation ago. The same efficiencies can be found in how we buy and sell airline tickets, reserve hotel rooms, and obtain services. Over time, these sorts of efficiencies decrease the cost of market modes of social coordination relative to hierarchical modes. They create an incentive to convert formerly hierarchical modes of social coordination into market-based ones.

For instance, we now “rationalize” decisions about where to attend college by means of statistical standards for measuring employment outcomes for graduates. The hope is that these standards will replace the family and community networks that once disposed (folded) young people toward certain choices. This shift toward market signals and away from individualized, non-standardized (and unequally distributed) modes of personal formation is evident throughout society. And it is accelerating, because it is endorsed by both liberals and conservatives as the better, more reliable mode of social organization.

A decrease in the relative cost of markets entails an increase in the relative cost of hierarchies. Modes of organization that increase in relative cost will be used less, over time, than modes that are relatively cheap. In modernity, the result has been that less and less space in society is available for hierarchies—and consequently for folding.

As the economic historian Karl Polanyi saw, this process of “marketization” is not natural. Hierarchy and society precede markets, according to Polanyi, and hierarchy is more natural and important for man than markets. Historically, markets have been subservient to civil society. Thus, in traditional societies, honor and virtue are prized more highly than wealth.

In his history of the “great transformation,” the period just before and during the Industrial Revolution, Polanyi stresses that the Industrial Revolution, by itself, did not cause marketization. In Great Britain, the state grew in concert with market interests, augmenting the Industrial Revolution by promoting markets at the expense of civil society and its subsidiary hierarchies. Among those subsidiary hierarchies were the town-based guilds and landed manors, which the state disempowered to make way for markets. The guilds and manors were intergenerational institutions that fused economic roles with social status. Their replacement by market organization represented a major social change.

It was but one change among many. As Polanyi shows, the British state sponsored one policy after another that was intended to destroy local communities and hierarchies and advance market interests. Without the state’s promotion of them, argues Polanyi, markets would have remained embedded in society, limited to particular and modest ends.

Polanyi’s history and its trajectory into the present are consistent with economists’ conceptions of the state. The “public choice” school of economics views state policies as resulting from the actions of bureaucrats, vote-seeking politicians, and other individuals operating within groups, each according to his rational self-interest. Polanyi noted that in Great Britain, just before and during the Industrial Revolution, actors within the state found it in their interest to accommodate business by globalizing capital markets, creating free labor markets, and disempowering guilds and landowners. Whether one considers these actions of the state good or bad (Polanyi shows that they were in many cases disastrous), Polanyi’s point is that markets were never “free”: Free markets in Britain were the creature of the state. Indeed, the great political project of the modern era has been to clear away the impediments to ever more expansive market activity.

There is another way to model the state as having its own goals. According to this account, attributable largely to the work of Mancur Olson, the modern state is, in effect, a highly developed form of the mafia. It is an agent with a territorial monopoly on taxation. It behaves in accord with its rational self-interest, which is to maximize government revenue.

Like the public choice model, the Olsonian model describes a state with strong incentives to augment markets at the expense of hierarchy. As Olson notes, the state has the power to tax all members of society. He calls this an “encompassing interest” because the state’s interest is in taxation, and taxation encompasses all citizens within a territory. By encouraging more market exchanges among citizens, the state expands the taxable pie, generating higher tax revenue. By contrast, social conflict disrupts commerce and decreases the size of the pie. For this reason, Olson’s model predicts that the state will sponsor clear property rights and effective contract enforcement. Commerce will become more attractive, increasing economic activity—and tax receipts. Thus the state will grow apace with capitalism, as indeed it has.

In an Olsonian model, there are other reasons for the state to sponsor market growth at the expense of hierarchical institutions. Hierarchies decrease the need for the state because they produce complex and complementary soul shapes. As Aristotle saw, the complementarity of well-folded souls gives rise to marriage and family, and then to kin and other supportive social networks. These networks not only satisfy demands for public and private goods—often better and more sensitively than the state can—but also provide stability. Hierarchical institutions are the state’s natural competitors.

Further, moralizing hierarchies are troublesome for profitable, and therefore taxable, commerce. They censure luxury and overconsumption, reminding people that honor is to be prized over wealth and that spiritual goods are more desirable than material goods.

Finally, the activities of hierarchical institutions are harder for the state to tax than markets. The goods produced by hierarchies are interior. They’re not easily measured. Thus, any taxation of a hierarchy must be a tax on the institution itself, rather than on its essential activity. This form of taxation is typically seen as oppressive. As such, it’s often resisted.

By augmenting markets, the state augments itself. The state hinders folding by promoting a shift of the market-hierarchy boundary line, to the disadvantage of hierarchies. If we regret this shift, then the question becomes: Does any institution exist that is equipped to counterbalance the state?

Such an institution would need to satisfy four criteria. First, it would need to be distinct from, and have a claim to authority separate from, the state. It would need to possess an authority that did not derive from the state itself. Second, it would need to have long experience with the state, often as an antagonist. Third, it would need to be a specialist in the folding of souls. Fourth and finally, its interest in human activity would need to be at least as encompassing, and perhaps more so, than the state’s.

The institution of marriage should satisfy these criteria. But it has become amorphous, and relies too heavily on the state for its institutional form—which is why it could be radically redefined by the state in the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision. That leaves the Christian Church, most notably in its Catholic institutional forms.

It is easy to see that the Church satisfies the first three criteria. The fourth—an interest more encompassing than that of the state—is less obvious. The Church professes to be universal. Her aim is to form all souls and lead them to salvation. Her universal character encompasses not only geography, but also time. The Church’s citizens include persons from all places and ages of history—the militant (currently here on earth), the suffering (currently in purgatory), and the triumphant (in heaven).

The Church’s universality transcends and limits the state. It follows that it transcends and limits the state-augmented market as well. Indeed, the Church in her social doctrine has little to say about particular political regimes, or kinds of regimes, and far more about questions of political economy. She has concerned herself with the market side (loosely understood) of the market-augmenting state.

Catholic social doctrine has long argued for a “family wage,” indicating a suspicion of market prices as the ultimate determinant of the price of labor. This suspicion is warranted. Labor markets influence the quantity and quality of folding in a society, and the price of labor (the wage) may not reflect the real costs of foregone folding.

The Church has also stressed that real property, not simply the ownership of intangibles such as stocks or bonds, is necessary for human flourishing. Catholic doctrine on property parallels Richard Weaver’s argument that property is a “substance . . . [that] is somehow instrumental in man’s probation.” As the soul unfolds and develops, it needs property. To own property means to be in relationship with it. That relationship involves maintaining property, modifying property, and bearing the psychic costs of neglecting property. Hence, property must be private (non-state) and at some level non-decomposable. As a “substance,” property is in many ways unyielding, and humans must conform to it rather than bend it to their will. The Church’s social doctrine therefore sees property as a practice for, and support of, human complementarity.

Finally, the Church’s social doctrine stresses subsidiarity and solidarity. Subsidiarity entails the proper empowerment of hierarchical institutions. Solidarity emphasizes complementary relationships: familial, kin, and other local networks. These principles restrain the market-augmenting state.

The ironies of our cultural moment are too numerous to count. In a democratic era, hierarchies are regarded as enemies of personal liberation. Yet at their best, they are the surest guarantors of mature, free, and complementary human souls, and thus of the good society. Meanwhile, both progressives and conservatives, in different ways and for different reasons, end up enhancing a state that has no loyalty to either solidarity or genuine freedom.

Rapid and sustained economic growth is relatively new in human history. The future of “humane” society may thus depend on the ability of a far older, more experienced, and often-derided player—the Church—to act as antagonist to the market-augmenting state. This, in turn, will depend on the willingness of Catholics and other religious believers to realign their identities and primary loyalties toward soul-forming origami, and away from the state and market. There are no guarantees that this can or will happen. But if it does, it will require sustained effort in a radically materialist age.

Timothy Reichert is an economist living in Denver. Francis X. Maier writes from Philadelphia.